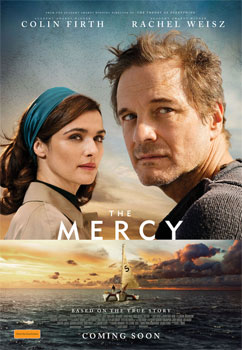

Colin Firth The Mercy Interview

"I am going because I would have no peace if I stayed." " Donald Crowhurst

Cast: Colin Firth, David Thewlis, Rachel Weisz

Director: James Marsh

Genre: Drama

Synopsis: Following on from his Academy Award® winning film The Theory of Everything, James Marsh directs the incredible true-story of Donald Crowhurst, an amateur sailor who competed in the 1968 Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in the hope of becoming the quickest person to single-handedly circumnavigate the globe without stopping. With an unfinished boat and his business and home on the line, Donald leaves his wife, Clare, and their children behind, hesitantly embarking on an adventure on his boat, the Teignmouth Electron.

Not long after his departure, it becomes apparent to Donald that he is drastically unprepared. His initial progress is slow, so Donald begins to fabricate his route. His sudden acceleration doesn't go unnoticed and he soon emerges as a serious contender in the competition. Donald's business partner, Stanley Best, had reminded him that he could pull out at any time, however, the consequences to his family from such a decision are unthinkable; Donald has given himself no other choice but to carry on. During his months at sea, Donald encounters bad weather, faulty equipment, structural damage and, the most difficult obstacle of all, solitude.

One by one, his fellow competitors drop out until it is only Donald left to challenge Robin Knox-Johnston, who is first to complete the round trip. As the pressure from what awaits him back home increases, Donald faces his toughest challenge, maintaining his sanity. When he receives word from his press officer, Rodney Hallworth, of the recognition and celebrations awaiting him upon his return, Donald's mind finally breaks.

The Teignmouth Electron is found abandoned off the coast of the Dominican Republic. Donald's scrawled logs are inside, filled with ramblings of truth, knowledge and cosmic beings. Back home, his wife Clare is left without a husband, his children without a father.

The Mercy

Release Date: March 8th, 2018

Colin Firth The Mercy Interview

Question: You were attached and committed to the project from very early on. What was it about this film that spoke to you?

Colin Firth: You don't have to have been to sea, you don't have to be a sailor, you don't have to be an explorer. You don't even have to have taken on anything particularly extreme in the obvious sense. I think people will recognise what it feels like to go further than you are truly able to, to take on something ambitious, risky and really dare to make a gesture like that in their lives, even if it's just in their relationships. I think they'll also recognise the idea of having rather random things seem to conspire against them. There are very few stories that really deal with that.

The traps that one can get into are so gradual and incremental that you don't see them until they're too big to do anything about. From my own life, that moment I should have turned back, is never something I can identify except in retrospect. I think when we were looking into this story, all the details, all the preparations, all the things that were going wrong, all the things that conspired against one particular individual, these would be the stories that applied to the heroes that we celebrate. Every time you hear about the guy who reached the top of Everest, the whole space programme or the first man to cross the desert or the ocean, if you study the stories of their preparation there were always things going wrong.

The narrative is interpreted completely differently if it ends happily than if it doesn't and I think sometimes there's a hair's difference between it going one way or the other.

Question: Did you have an immediate connection with Donald Crowhurst and that duality he felt between his public and private persona?

Colin Firth: I think we all have a public and a private persona, perhaps more than that. I think we live in a time where we are all quite obsessed with broadcasting ourselves, in some way or other, through social media. Perhaps that's always been the case, but we now have new tools for doing it. We take photographs of ourselves, we post versions of ourselves and we create profiles of ourselves.

If the profile becomes a big one and in cases where people are very well known and they develop a reputation, whether it's politicians or people in the arts, I think it can become a sort of a burden. I think you can be trapped by your reputation whether it's a good one or a bad one.

In some ways, when I read this story, I felt that was something that would resonate with a lot of people.

Question: Do you think Donald Crowhurst was fated in some way?

Colin Firth: No, I don't think so. Fate, I don't even think it's about that. If you believe in fate you're welcome to look at it through that lens but no, I think it's random. We'd be telling a different story, had one piece of equipment been on the boat, if one day's weather had been different, the business arrangements worked out differently. But it's almost impossible to deconstruct the -what-ifs'.

There are a lot of random elements. It's a whole other discussion when you look at what makes somebody want to take on something so extraordinarily difficult and dangerous. I reflected on the main differences between me and Donald Crowhurst, his virtues and his strengths. I wouldn't dare do what he did. I wouldn't have the ability to apply myself to a task like that. I wouldn't be able to design that boat, I wouldn't have the mathematical skill, I wouldn't have the sailing skill, and I wouldn't have the knowledge of astronomy and navigation. All the other things could be me and the problems could be ones any of us encounter. I just wouldn't have the resources that he had to get as far as he did and do what he did. It was a most extraordinary thing.

Even to this day, what Crowhurst did is unparalleled because, although people have gone round the world and have endured all sorts, I don't know if it's even possible now to construct a challenge with that sort of adversity. I think it was Robin Knox-Johnston who said -they were like astronauts'. They were sailing across a frontier, because there was no GPS and the ways of finding you were scant. They had a radio but their communications were rudimentary by today's standards. They were sailing with the same sort of equipment that Captain Cook was using. It hadn't moved on much. It was sextant, barometer, compass, wind vane and your own skills. You could get lost and no-one would be there to rescue you, unless you were very fortunate and someone was within range of your Morse Code.

I'm certainly not saying anything to diminish the extraordinary feats of what people do today, but the idea of that degree of isolation for that length of time, I can't think of how one could parallel it now, because the communications are so comprehensive. I understand that there is some sort of plan to reproduce this race for the anniversary in a couple of years' time, and if they decide they're not going to use GPS but to use precisely the tools and technology that were available in the 1960s, there are still so many satellites up there, you can't really get so completely and utterly lost and out on your own, as you could then.

Question: It took place at a time in history when men could reinvent themselves and the classes were breaking down. It's perhaps for that reason that Crowhurst's story is such an enduringly fascinating one. Did you ask -why did he do it?'

Colin Firth: Well, I just had to accept at face value what he said about it himself. But I think that by not accepting the challenge that it would have affected something within him. It makes sense to me. I think he did have the ability to do it. He had more ability than most of us to create the possibility in terms of boat design, in terms of his sailing ability and in terms of his navigational ability. Things just went wrong.

There's a very fine line between succeeding and just not succeeding. Nine guys went out on that race and only one actually came home, all for various reasons. People do take on extraordinarily dangerous things. I can understand why Crowhurst did it. As the famous saying goes, why does anyone undertake these things: 'Because it's there." (*quote from explorer George Leigh Mallory).

Question: There is obviously a wealth of research material on Crowhurst. Can you talk us through your own research?

Colin Firth: I just went through everything that was available. It started with the script, then the documentary Deep Water and then the book, The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst by Tomalin and Hall. The book is an interesting read. Even before I became partial and tendentious in my own views and felt so personally drawn to Donald Crowhurst, the book – which is brilliant journalism and very rigorously written – I felt was unfair on him, in ways that at times it was just to do with the subtlety of inflection. I thought they were uncharitable interpretations. One has to remember it was written very soon after the events, and by the Sunday Times journalists, and I think there was an agenda, or at least they were writing from a particular point of view. But, it was certainly very, very compelling in terms of information.

There's also the archive footage and there are the tapes that Donald Crowhurst made during his voyage for the BBC. They were fascinating partly because of some of the information he was able to give about daily life. He focussed on his cooking regime, on what he was seeing, on the weather, his problems with his transmitter. He sang a lot - Christmas carols, sea shanties, ballads. He played his mouth organ. Paradoxically, you can feel you're in the company of a man who's completely alone. But they are in some ways much more his public self. I think it was even observed by people who were close to him, that the tapes didn't really quite sound like him.

Then you have the logs, some of which are just ship's log - positions and records of the things you're supposed to put in a ship's log. Some of it was more to do with his thoughts and were very, very rigorous and stark breakdowns of his practical problems - calculating his chance of survival if he went forward as being at best fifty-fifty. There are also very realistic and professional lists of things that needed doing - ones that might have solutions, and ones that couldn't possibly have solutions. You start to see the extent of his problems and the trap he was in through a very hard-headed analysis. I'm an amateur but he lays it out so clearly that you look at it and think, -No-one could go forward. You have to stop.' But the conditions of stopping were so brutal. That was the kind of pressure, whether it's the pressure of the public eye or whether it's something about, what you've had to summon in yourself to embark on something like that, followed by the solitude and everything you're up against. I don't think any of us can possibly understand that.

I think it's very important to note what Robin Knox-Johnston said specifically about Donald Crowhurst: -No-one has any right or is in any position to judge unless you've experienced that solitude, unless you've experienced the elements in that way'. In telling this story, it's my hope that it can be distilled into that particular objective. When I read it, it was a feeling that we are in no position to judge and that it's no good for us, or anybody to judge.

It's very interesting to read around and look at the experiences of the other sailors in the same race, because there were sailors who were considerably less experienced than Donald Crowhurst. Chay Blyth hadn't sailed in his life - he went out with an instruction manual and a boat behind him yelling out instructions. He'd rowed across the Atlantic but he hadn't sailed and now he's a legendary sailor. Ridgeway who'd rowed with him, the solitude got the better of him, very early on in the voyage, and he quit. Carozzo was up against similar problems to Donald Crowhurst in that the deadline was looming and he did something that was rather ingeniously strategic, in that he met the deadline by sailing on the day of the deadline, and then he dropped anchor off the coast of the Isle of Wight and spent another two weeks doing what he needed to do, but the stress of it all gave him a stomach ulcer and he had to pull out.

Question: The truly unique thing about your job is in how close you have to get to a character and how you pour that empathy into it. What's that experience like? Did you hear Crowhurst's voice?

Colin Firth: I literally heard his voice because I listened to the tapes continually. I went into the material continually. Actors have to withhold judgement. It's not our job to judge at all – they even tell you this at drama school. Other people will probably make their own judgements and again it's usually a pretty easy, facile thing to do. As an actor, we have to inhabit and justify a character and there's nothing particularly strange or airy-fairy about that.

As actors, we're just doing it from the inside and to some extent you feel you've walked a mile in someone's shoes. But there's always that sense that you haven't reached it, particularly if you're telling the story of a real character. When the character's fictional you can satisfy yourself, hopefully, that you own it, that you've created something which is much more yours. When the character's real it's partly a privilege or just sheer good fortune and is helpful to have the made material there. If the character's somebody that you're able to meet, you have all that to inspire you and to work off. But to me it's also a reminder that you're not him. It does put you in a very strange and very close relationship.

Question: There must be a sense of duty as audiences will take this as the definitive account of Donald Crowhurst's story?

Colin Firth: Well, there is and it's troubling because of the limitations of fictional filmmaking. You can't scrupulously observe all the facts. You have to mess around with the chronology in order to distil it into its three acts. It's frustrating for all of us but you are still trying to keep it as honest as possible. You hope that in taking a compassionate approach, we'll end up telling the story in a way that engages people's sympathy and understanding, even if it's not claiming to be an exact account of what happened.

My hope is that if a film breaks through, it becomes part of a conversation that will lead people to want to look a little harder. There's a documentary, there's a book and there are different versions of all of this. Even journalism has to take an angle, however impartial it is. Even a photographer who's taking a picture of an event has to stand somewhere. So, in some ways there's no such thing as a completely neutral, three hundred and sixty degree perspective on anything. I just think you've got to do it with as much compassion and as much imagination as you can muster really.

Question: Let's talk about Crowhurst's actual experience on that boat. There's obviously the very practical, technical side to it, but there's the spiritual experience too. Do you think Don ever got close to being at one with himself?

Colin Firth: I think he did. I think he got more than close to it. Just going from what he himself said. We can't guess more than beyond what we have from his own words. In one of his recordings, he's musing and reflecting on life and some of the more philosophical questions that are associated with everyday life that you wouldn't perhaps have time to do if you were back home, in amongst it all and he was aware that -Watching the sun go down in the tropics, does lead one to deeper thoughts'. He asks our pardon for rambling on the tape, but these are the sorts of things that occur to him, and this is only what he's saying to the BBC. I think it's inevitable that the parameters of your world would be different, quite literally. You are in a tiny, tiny little space - a forty-foot boat, with a cabin, which is shockingly small. So the cabin is utterly claustrophobic and you're right between that and infinity. So you're experiencing extreme space and lack of space.

What relationships have you got? Human relationships are limited to radio, whether it's BBC World Service, Voice of America, or Morse code communication or the radiotelephone. You are creating a relationship with your environment that means you probably won't be ever quite the same again when you come back. He had books but he didn't take any fiction or any novels. The reading material he did take was Einstein's Theory of Relativity. He took books about sailing and he had his Admiralty charts but the rest of it was about relationships with celestial bodies - the sun, the moon, the stars, the horizon, the light, the wind, obviously the sea, and his own boat. Your boat takes on a persona. The boat becomes a living thing to you.

Solitude, the physical environment, the elements, celestial bodies, whatever marine life, whatever books, whatever bits and pieces you get through the radio, that becomes your entire universe.

One of the last scenes we shot was a moment based on Crowhurst's own recordings where he finds a sea creature, a little fish, in our story it's a Sargassum fish. He describes them as being like little Cornish pasties, which he found absolutely delightful. He tried to keep one as a pet but it died in the bucket that he kept it in. In reality he also developed a relationship with a migratory bird that landed on his ship and he wrote a poem about it called The Misfit. He wrote a rather wonderful piece in his own personal log, describing the bird, and clearly identifying with it in some way, because it wasn't a seabird, it just landed on the boat because the nearest land was a couple of thousand miles away. It sat there for a while and rested and he hoped that the bird would take off in the direction of the closest land but it didn't. He clearly connected with that image. As I understand the character, there's a constant feature of this gentleness and it's in everything he writes. There's compassion and decency and he values reason and honesty. I think it was very important to him for things to be fair and I think that's partly why the trap he got himself into must have been such a turbulent one. Crowhurst's imagination was probably a big enemy to him. He talked about the noise. He also said -Everything on the boat's wet. It's not damp. It's dripping in your ear all the time'. You imagine spending a bit of time down in the cabin where it's cosy but when we shot the storm scenes, I went down in the cabin a lot, but I never battened down there for long when we were at sea, because of the waves, the claustrophobia and nausea, you want out of there so quickly. It was horrendous…talk about lying at the bottom of a mineshaft in an earthquake! It's extraordinary what Crowhurst was made of and that he stayed coherent for as long as he did. He made it to the Falklands and back. I mean most sailors wouldn't dream of a trip like that.

Question: The endeavour was a peculiarly English thing to do don't you think?

Colin Firth: Oh it's very English although it's not exclusively English – the Americans have their own version of having a go but they were going to the moon. There's a British maritime obsession, with Chichester and Alec Rose and all these guys. It's partly because we're an island, it's partly because of maritime history, and it's partly because we had a bit of a self-esteem problem in the 1960s. We couldn't afford the space programme so all you need is a guy on a boat and we'd prove our mettle.

Question: Was being out there on the boat in the nothingness a good exercise from a performance viewpoint?

Colin Firth: Yes, it was interesting but you're in collaboration. What's quite nice about being the only person in front of the lens is that it brings you quite a lot closer to the work that's going on the other side of the lens. It sometimes became a little bit of a huddle between James Marsh, Eric Gautier (cinematographer) and myself in the decision-making process. You've got one guy with a handheld camera, a director orchestrating things and bouncing the ideas, and then one guy on the other side of that camera so we were feeling our way together, often without dialogue. It was for us to discover.

Then of course we had the elements to deal with and they don't cooperate – when you want bad weather you've got smooth weather. James didn't want to film in tanks, he wanted to film on real sea and we did that. We had to use the tank for a couple of moments, night shoots in the storm but we were out at sea generally. The sea was so still on one particular day it was even stiller than the tank, it might as well have been a swimming pool, which is frustrating because on a day when you want calm of, course it's rocking. A lot of things can conspire against you when you're filming and the number of things that can go wrong when the clock is ticking, that's notorious in the filmmaking process.

When you've got land in the background that you're trying to hide, and something goes wrong with the camera and you've got to do it again but the land's now even more in the background, you can't just say, -Can we just move the boat back couple of metres and do that again?' You've got to tack back and by the time you've done that, which might take an hour, the light's changed and the wind's changed.

You have to use your imagination and tailor the nature of the scene to the conditions. We did an awful lot of cabin interior stuff in the studio, which was surprisingly claustrophobic. I'd imagined we'd have half a cabin and we'd be shooting from the outside but it was closed in and they'd just make a little hole for the camera to come in. It was set up so that it could rock violently so we'd actually get home in the evenings with the room still rocking.

Question: What were your original conversations with James Marsh about what type of film this was going to be?

Colin Firth: The script gave us the shape. It doesn't focus on the other people in the race, they don't appear in the film, they just exist in the background and they're reported on, their presence is felt but the film doesn't focus on them directly. It does take us into the family life and it focuses on Rodney Hallworth the press agent who is an important character, as is Stanley Best the sponsor.

I think it's as much about what inspires the desire to do it and what creates the problems before the journey starts. We're probably about half way through the film before the race begins, for Donald. It's every bit as interesting to see the trajectory towards the departure.

Question: There's a mechanism at work and chain of events that's forcing his hand to embark on the journey when he's not really ready isn't there?

Colin Firth: They're his decisions, but often it's about the entanglements that your own decisions create. Then, there are his attempts to solve problems as they go - they're ingenious and there are signs of resolution, determination, resourcefulness and ingenuity. I for one found immense admiration and sympathy for him every step of the way. I could see each problem as it occurred, however trivial it was, it is also rather diabolical - the whole notion of Sod's Law. He made a very sincere attempt to face up to the reality that the race was not going to be practical. He explicitly attempted to pull out – it's mentioned in the documentary. The night before he left he said to Hallworth and Best, -The boat's not ready.' He knew that but he had to go. They told him he had to go. The contract that he had signed meant forfeiting his house and his business if he didn't go, indeed if he didn't finish either. So he had to set out.

He was persuaded to fix his problems as he went and he might have succeeded in doing that had the piece of tubing been on board that was supposed to pump out the floats that were leaking. Everyone's boats experienced leaks but he had to bail out with a bucket because one item that had been chased down wasn't on board just because of the last-minute rush to get everything ready. There was a pile of important stuff left on the jetty that should have been on the boat and there were things on the boat that he might not have needed. Moitessier was apparently throwing stuff overboard throughout his voyage. We're trying to offer a study of what led up to the day of departure and the traps you get into with a business transaction when someone's giving you a lot of money to help you, what are the conditions? What kind of traps does that put you into?

Then of course there was the press who could be a great tool to use in his favour because that's what brought in sponsorship. But they were an unwieldy instrument. It's not something you control and I think the mythologised version of Donald Crowhurst that was growing before he left, didn't leave him particularly comfortable, but it was something that his press agent was using to facilitate the whole thing. Before he knew it, stories of his progress were being vastly exaggerated without his having anything to do with it.

Question: Screenwriter Scott Z. Burns said that he's very aware that in our culture right now there's a kind of a gloating at failure, whether it's the tabloids or social media and that in writing this take on the Crowhurst story, he hopes it to be something of an antidote.

Colin Firth: Absolutely, I think this is saying, -Who are you to judge?' It's a terrible reflex, so I think there's a side of us, when the mob forms in social media or in the comments sections that we're no better than playground bullies. It's a way of distancing ourselves from the spectacle of someone who's been humiliated or who's fallen short of something. There's safety in the numbers of smug people who aren't going through that at the moment. It's a very, very ugly phenomenon. While I was shooting I read Jon Ronson's book, So You've Been Publicly Shamed, where he talks about this phenomenon. It's almost as if social media has revived the old idea of the stocks and the pillory where public humiliation was a part of our legal sanction system. It's quite extraordinary. I mean the slightest gaff now will be punished on such a grand scale. It seems that people aren't satisfied until the person is completely ground into the dust. I hope anything that challenges that reflex is probably a good thing. I think that incredibly facile and unfair judgments have been applied to the Crowhurst story. My hope is that by taking people through it on a personal level and in revealing some of the nuances that people won't be able to do that. When the cast all sat down and read the whole script that was certainly the abiding feeling afterwards. People didn't speak for a few minutes. I think the one thing everybody agreed on was an outpouring of compassion for everybody concerned really in the story and just how dare we judge?

Question: Rachel Weisz as Clare Crowhurst is a great piece of casting. What does she bring to the performance and how do you see Clare Crowhurst?

Colin Firth: Rachel is, as Clare Crowhurst herself is, a fiercely intelligent, insightful and strong person. I think she brings a wryness and an alertness about her that can see the complexities of what Donald wants to do. She's afraid for him and she wishes that he wasn't doing something so dangerous. She believes in him and in his ability to see it through. I don't think she was wrong to believe in that.

Clare was very, very keenly aware that this was something he really needed to do and that not doing it would be as dangerous to him as doing it. I think you need to have a great deal of love for somebody to embrace all that. I can only speculate as far as our interpretation goes but I think that Rachel would probably concur with all that.

Question: You shot the family scenes before the boat scenes. Did that help establish the close relationship he had with his family?

Colin Firth: I think it would have been very difficult if I'd had to shoot the boat stuff before I met anyone who was playing the family. We formed a relationship. You always hope that when you are doing a film about a family that you can form something of a family in the process and we did start to enjoy each other's company. The kids were absolutely great. It helped that they were talented and disciplined, that's not to be taken for granted. But they were just such lovely company, and they seemed to understand what we were all trying to do in a given scene. It was also very important to me in the few scenes we had to stage was to establish a very happy family, a truly wonderful father. The children adored him. He was imaginative and incredibly committed to them. I think in some ways I think his venture was for them as well.

We can very easily pronounce judgement on why a man with a family would take such great risk. Well, people do need to take risks and some of them have families, and I think he believed he could do it, that he would come home, and that it would be a gift to his family, from a financial point of view as well. He hoped to come back as the father he wanted to be to them. A lot of this is me imposing what my motives would be, because I think every time you play a role, to some extent, you want to be that character and the whole story and this setup is as if it were me.

I honestly think that Crowhurst did almost everything with his family in mind.

Question: What experience of sailing did you have already and what did you have to learn?

Colin Firth: I had almost no experience whatsoever. My uncle Robin took me sailing when I was a little boy. The last time I did it, I must have been about eight years old. He came to visit me on the set as he's down in Devon and he still goes out sailing every weekend. That was my connection as he's the same generation as Donald and Clare Crowhurst and he knew all about it.

Obviously there was a bit of a rush to get me acquainted with the basics in order to do this film. I did everything from going out on the boat that we had built for the film, to single-handing on a little catamaran when I was on holiday on an island off the coast of Cambodia and that's when I started to love it. Just being on my own, on a tiny craft, just beginning to get acquainted with your relationship with the wind really. It was a very simple boat, it didn't have a jib, didn't even have a boom. But it did do what boats do in relation to the wind. I understood why, particularly on a tiny little multi-hull for instance, because it struggles into the wind. I learned why it performs very well on a reach. These things were just theory and in some ways if I'd had my first lessons on a big boat with a crew, it might have remained theory. I was only out for an afternoon at a time but it started to make sense to me. Then of course I started to realise how many people I know are truly avid sailors and everything I've just said is real potted beginner's stuff.

If you do sail then this stuff will sound so green and ignorant, and if you don't sail, even the basics sound like some sort of extraordinary foreign language. They were very patient with me, but I had to learn their language and all sorts of little rules. I never had to really single-handedly, meaningfully sail the boat, certainly not without somebody on board, waiting to help out if anything went wrong. But I did, very much enjoy learning the basics in the end. I don't think it's got a future for me though!

Question: Crowhurst set sail from Teignmouth and you filmed there. The event is in living memory for a lot of people who still live there. How did that feel?

Colin Firth: The people were really very lovely down there. We were made to feel extremely welcome. People tolerated a great deal. It's not convenient to have a film crew in your town. There was an awful lot of affection for Donald Crowhurst and for this story. There were older people who told me that they'd known him and were very anxious to share their experiences and their anecdotes. I think his story is now regarded with immense sympathy. Maybe it always was, but we were very struck by how people felt both sympathy and admiration for Donald Crowhurst.

We were treated with nothing but grace and good humour. Devon is the most beautiful county and I think filming in Teignmouth might have been one of the highlights of our shoot really.

Question: What characterises James Marsh as a director?

Colin Firth: He's very bright, he's extraordinarily committed and very collaborative. At times I think we both went down a bit of a rabbit hole, talking through ideas and trying to resolve conflicts in terms of storytelling and what's possible, what's important and what has to be sacrificed. He seemed to welcome that collaboration. I found the partnership with James to be the perfect one for a story like this, really. Once it was just me in front of the camera, it became even more of a kind of nexus that I was very dependent on. It wasn't just the two of us obviously, it was our relationship with not just camera, not just sound, but with the marine guys as well, as they're the experts.

James is very exhilarating company and he's a very exhilarating collaborator. I think it's one thing to have very clear ideas about what you want to do, it's another thing to have that coupled with flexibility because they often exclude each other.

Question: What was the experience of shooting in Malta like?

Colin Firth: Malta obviously suited our needs in so many ways, because they have this extraordinary tank, and the word -tank' doesn't really tell a story as to what it is. It's a big infinity pool with the sea at the end of it. The effects you can create there are a very dramatic spectacle, where these pumps and water cannons could basically create a storm. It was fantastic for shooting the warmer climes. That's where we shot all the Sargasso Sea stuff and all the summer zone material out at sea. It's a beautiful island and so basically it's an ideal spot to shoot. If you're shooting on boats, I don't think you could be in a better environment really.

The Mercy

Release Date: March 8th, 2018

MORE