Ken Loach I, Daniel Blake Interview

Ken Loach I, Daniel Blake Interview

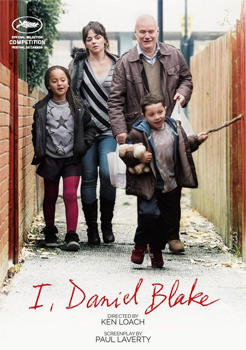

Cast: Dave Johns, Hayley Squire

Director: Ken Loach

Genre: Drama

Rated: MA

Running Time: 100 minutes

Synopsis: Daniel Blake (59) has worked as a joiner most of his life in Newcastle. Now, for the first time ever, he needs help from the State. He crosses paths with single mother Katie and her two young children, Daisy and Dylan. Katie's only chance to escape a one-roomed homeless hostel in London has been to accept a flat in a city she doesn't know, some 300 miles away.

Daniel and Katie find themselves in no-man's land, caught on the barbed wire of welfare bureaucracy as played out against the rhetoric of -striver and skiver' in modern-day Britain.

I, Daniel Blake

Release Date: November 17th, 2016

Paul Laverty: Writer

Paul Laverty: Writer

Rebecca (producer) and I didn't think it would take Ken long before he wanted to sink his teeth into something fresh after Jimmy's Hall, despite the rumours. It didn't. It was a rich cocktail that seeped into what became I, Daniel Blake.

The sustained and systematic campaign against anyone on welfare spearheaded by the right wing press, backed by a whole wedge of poisonous TV programmes jumping on the same bandwagon caught our eye. Much of it was crude propaganda, savouring the misery of often pathetic characters in the most prurient fashion. And all the better if they had a drink problem, a sure sign of them wasting precious taxpayers' money.

Little wonder it led to a spectacular aberration. Studies found that the average person thought that in excess of 30% of welfare payments were claimed fraudulently. The truth is that it is 0.7%. It was no surprise to find out that many people on benefits had been insulted and humiliated with a significant number being attacked physically.

This manipulated distortion dovetailed perfectly with the austerity narrative by the government and welfare cuts became a prime target. Who can forget Osborne's speech on the 'closed curtains" of the hordes of skivers still asleep in the early morning at the last Tory party conference? Another fact: only 3% of welfare budget goes to the unemployed while the elderly, the Tory preferred constituency, takes 42% in pensions.

But the immediate spark for this story started with a call I got from Ken to join him on a visit to his childhood home of Nuneaton where he has close connection with a charity that deals with homelessness. We met some terrific workers and they introduced us to some of the youngsters they were working with. One lad whom they had recently helped shared his life story with us. It was his casual mention of hunger and description of nausea and lightheadedness as he tried to work (as usual, zero hour contracts with precarious work on an ad hoc basis) that really struck us.

As Ken and I travelled the country, one contact leading to another, we heard many stories. Food banks became a rich source of information. It struck us that when we made My Name Is Joe or Sweet Sixteen, or even going further back to Ken's earlier films, one of the big differences now was the new world of food banks.

As more and more stories came to light we realised that many people are now making a choice between food or heat.

We met a remarkable man in Scotland, principled and articulate, desperate to work, who refused point blank to do meaningless workfare, who was given endless sanctions by the Department for Work and Pensions. He never turned his heating on, survived on the cheapest canned food from Lidl and nearly got frostbite in February 2015.

We heard stories of 'revenge evictions" i.e. tenants thrown from their homes for having the temerity to complain of faults and poor conditions. We were given examples of the poor being moved from London and offered places outside the capital, a species of social cleansing. And it was impossible not to sense the echo from some fifty years back when Ken and colleagues made Cathy Come Home although this was something we never talked about. Breaking the stereotypes, we heard that many of those attending the food banks were not unemployed but the working poor who couldn't make ends meet. Zero hour contracts caused havoc to many, making it impossible to plan their lives with any certainty and leaving them bouncing between irregular work and the complexity of the benefit system.

Another significant group we spoke to in the food banks were those who had been sanctioned (i.e. benefits stopped as punishment which could be from a minimum of a month to three years) by the DWP. Some of the stories were so surreal that if we had them in the script they would undermine credibility, like the father who was sanctioned for attending the birth of his child, or a relative attending a funeral, despite informing the DWP of the reasons. Literally millions have been sanctioned and their lives, and those of their children, thrown into desperation by a simple administrative decision. Criminals are treated with more natural justice, and the fines are often less than what benefit claimants lose when hit by a sanction.

This led us to another very important group of people who risked their jobs to help us. Workers inside the DWP who spoke to us on an anonymous basis who were disgusted by what they had been forced to carry out in relation to sanctions. One worker in a Jobcentre showed me a print-out that showed how many sanctions he and his colleagues had given out, together with a covering letter from his senior manager, stating that only three 'job coaches" had carried out enough sanctions in the past month. If they didn't carry out more sanctions they would be threatened with the Orwellian sounding PIP - 'Personal Improvement Plan". For the record, let me address those senior managers of the DWP and their political bosses who have given evidence before the UK and Scottish Parliaments stating that there are no targets for sanctions. You are brazen-faced liars hiding behind legalese, and your workers know it. Specific numbers might not have been given, but clear demands and 'expectation" were implicit and they were forced to get the numbers up.

This led us to another very important group of people who risked their jobs to help us. Workers inside the DWP who spoke to us on an anonymous basis who were disgusted by what they had been forced to carry out in relation to sanctions. One worker in a Jobcentre showed me a print-out that showed how many sanctions he and his colleagues had given out, together with a covering letter from his senior manager, stating that only three 'job coaches" had carried out enough sanctions in the past month. If they didn't carry out more sanctions they would be threatened with the Orwellian sounding PIP - 'Personal Improvement Plan". For the record, let me address those senior managers of the DWP and their political bosses who have given evidence before the UK and Scottish Parliaments stating that there are no targets for sanctions. You are brazen-faced liars hiding behind legalese, and your workers know it. Specific numbers might not have been given, but clear demands and 'expectation" were implicit and they were forced to get the numbers up.

Food. Heat. House. The basics, from time immemorial. We knew in our gut this film had to be raw. Elemental.

There were endless possibilities. The characters could have been similar to the young people in Nuneaton scrambling around, hovering over homelessness on zero hour contracts. They could have been disabled, as we found out from experts the disabled have suffered on average six times more than any other group from the government's raft of cuts, a truly staggering scandal. Many of those sanctioned have been psychologically vulnerable suffering from depression and other mental illnesses. In the memorable words of one civil servant, the easy targets were 'low-hanging fruit" which perhaps could be the title of another poignant ballad to join Billie Holiday's.

The world of benefits is very complicated and changing all the time especially with Universal Credit on the horizon. It took some figuring out. But another key group that caught our attention were those men and women who were sick or injured and who had applied for Employment Support Allowance. The medical assessments for this benefit had been subcontracted to a French company, and then in turn to an American multinational after a series of scandals. The stories we heard, and the practices revealed, were legion. One furious young doctor told me of one of his patients who was dying of cancer, could barely walk, who was deemed 'fit for work." One day he fell at home and cut his head. The was called but he refused to get in as he was signing on the next day at the Jobcentre and feared a sanction that would stop his benefits. He died about three months later. What needless misery and humiliation was caused to this older man in his last days.

All of these people deemed fit for work are forced to spend 35 hours a week looking for work. In some parts of the country there were as many as 40 people for each job advertised. One academic informed me that over the course of the last Parliament there was roughly a variation of 2.5 to 5 claimants for every job advertised. Sisyphus came to mind.

Daniel Blake and Katie Morgan are not based on anyone we met. Scripts can't just be copied and transported from the food bank or the dole queue. Dan and Katie are both entirely fictional, but they were infused with all of the above and more. They were inspired by the hundreds of decent men, women and their children who shared their intimate stories with us. Faces of articulate intelligent people now come to mind, frightened people, older people tormented by the complexity of the system and new technology, (many of the staff within the Jobcentres told us they would like to have helped more but were prevented by managers obsessed with reducing 'footfall" from doing so) young people who had lost hope far too early, some I remember trembling with anxiety as they tried to summarise their predicament, and many doing their best to maintain their dignity caught up in something misnamed as welfare which had all the hallmarks of purgatory. And yes, you opportunist sanctimonious commissioning producers of the crass benefits TV programmes fanning hatred and promoting ignorance, there were some drinkers and addicts with chaotic lives and odd tattoos.

There has always been a vicious streak of state bullying in our society when it comes to treating the vulnerable. All we have to do is remember the workhouses of the 19th century that insisted on splitting up mothers and fathers from their children just to make sure the gruel was tempered by sufficient cruelty.

The Rev Joseph Townsend, an 18th century vicar, summed it up. 'Hunger will tame the fiercest animals," he wrote. 'It will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjection... it is only hunger which can spur and goad the poor on to labour."

Interview with Ken Loach, Director

Interview with Ken Loach, Director

Question: There were rumours that Jimmy's Hall was going to be your last film. Was that ever the case, and if so what persuaded you to make I, Daniel Blake?

Ken Loach: That was a rash thing to have said. There are so many stories to tell. So many characters to present... Question: What lies at that root of the story?

Ken Loach: The universal story of people struggling to survive was the starting point. But then the characters and the situation have to be grounded in lived experience. If we look hard enough, we can all see the conscious cruelty at the heart of the state's provision for those in desperate need and the use of bureaucracy, the intentional inefficiency of bureaucracy, as a political weapon: 'This is what happens if you don't work; if you don't find work you will suffer." The anger at that was the motive behind the film.

Question: Where did you start your research?

Ken Loach: I'd always wanted to do something in my home town which is Nuneaton in the middle of the Midlands, and so Paul and I went and met people there. I'm a little involved with a charity called Doorway, which is run by a friend Carol Gallagher. She introduced Paul and me to a whole range of people who were unable to find work for various reasons – not enough jobs being the obvious one. Some were working for agencies on insecure wages and had nowhere to live. One was a very nice young lad who took us to his room in a shared house helped by Doorway and the room was Dickensian. There was a mattress on the floor, a fridge but pretty well nothing else. Paul asked him would it be rude to see what he'd got in the fridge. He said, 'No" and he opened the door: there was nothing, there wasn't milk, there wasn't a biscuit, there wasn't anything. We asked him when was the last time he went without food, he said that the week before he'd been without food for four days. This is just straight hunger and he was desperate. He'd got a friend who was working for an agency. His friend had been told by the agency at five o'clock one morning to get to a warehouse at six o'clock. He had no transport, but he got there somehow, he was told to wait, and at quarter past six he was told, 'Well there's no work for you today." He was sent back so he got no money. This constant humiliation and insecurity is something we refer to in the film.

Question: Out of all the material you gathered and the people you met, how did you settle on a narrative?

Ken Loach: That's probably the hardest decision to take because there are so many stories. We felt we'd done a lot about young people – Sweet Sixteen was one – and we saw the plight of older people and thought that it often goes unremarked. There's a generation of people who were skilled manual workers who are now reaching the end of their working lives. They have health problems and they won't work again because they're not nimble enough to duck and dive between agency jobs, a bit of this and a bit of that. They are used to a more traditional structure for work and so they are just lost. They can't deal with the technology and they have health problems anyway. Then they are confronted by assessments for Employment and Support Allowance where you can be deemed fit for work when you're not. The whole bureaucratic, impenetrable structure defeats people. We heard so many stories about that. Paul wrote the character Daniel Blake and the project was under way.

Question: And your argument is that the bureaucratic structure is impenetrable by design...

Question: And your argument is that the bureaucratic structure is impenetrable by design...

Ken Loach: Yes. The Jobcentres now are not about helping people, they're about setting obstacles in people's way. There's a job coach, as they're called, who is not allowed now to tell people about the jobs available, whereas before they would help them to find work. There are expectations of the amount of number of people who will be sanctioned. If the interviewers don't sanction enough people they themselves are put on -Personal Improvement Plans'. Orwellian, isn't it? This all comes from research drawn from people who have worked at the DWP, they've worked in Jobcentres and have been active in the Trade Union, PCS – the evidence is there in abundance. With the sanctioning regime it means people won't be able to live on the money they've got and therefore food banks have come into existence. And this is something the government seems quite content about – that there should be food banks. Now they're even talking about putting job coaches into food banks, so the food banks are becoming absorbed into the state as part of the mechanism of dealing with poverty. What kind of world have we created here?

Question: Do you feel it's a story that speaks mainly to these times?

Ken Loach: I think it has wider implications. It goes back to the Poor Law, the idea of the deserving and the undeserving poor. The working class have to be driven to work by fear of poverty. The rich have to be bribed by ever greater rewards. The political establishment have consciously used hunger and poverty to drive people to accept the lowest wage and most insecure work out of desperation. The poor have to be made to accept the blame for their poverty. We see this throughout Europe and beyond.

Question: What was it like going to film in food banks?

Ken Loach: We went to a number of food banks together and Paul went to more on his own. The story of what we show in the food bank in the film was based on an incident that was described to Paul. Oh, food banks are awful; you see people in desperation. We were at a food bank in Glasgow and a man came to the door. He looked in and he hovered and then he walked away. One of the women working there went after him, because he was obviously in need, but he couldn't face the humiliation of coming in and asking for food. I think that goes on all the time.

Question: Why did you decide to set the film in Newcastle?

Ken Loach: We went to a number of places – we went to Nuneaton, Nottingham, Stoke and Newcastle. We knew the North-West well having worked in Liverpool and Manchester so we thought we should try somewhere else. We didn't want to be in London because that has got huge problems but they're different and it's good to look beyond the capital. Newcastle is culturally very rich. It's like Liverpool, Glasgow, big cities on the coast. They are great visually, cinematic, the culture is very expressive and the language is very strong. There's a great sense of resistance; generations of struggle have developed a strong political consciousness.

Question: Describe the character of Daniel - who is he and what is his predicament?

Question: Describe the character of Daniel - who is he and what is his predicament?

Ken Loach: Dan is a man who's served his time as a joiner, a skilled craftsman. He's worked on building sites, he's worked for small builders, he's been a jobbing carpenter and still works with wood for his own enjoyment. But his wife has died, he's had a serious heart attack and nearly fell off some scaffolding; he's instructed not to work and he's still in rehabilitation, so he's getting Employment and Support Allowance. The film tells a story of how he tries to survive in that condition once he's been found -fit to work.' He's resilient, good humoured and used to guarding his privacy.

Question: And who is Katie?

Ken Loach: Katie is a single mother with two small children. She's been in a hostel in London when the local authority finds her a flat in the north where the rent will be covered by her housing benefit – that means the local authority doesn't have to make up the difference. The flat's fine, though it needs work, but then she falls foul of the system and she's immediately in trouble – she's got no family round her, no support, no money. Katie is a realist. She comes to recognise that her first responsibility is to survive somehow.

Question: Much of the story deals with suffocating bureaucracy. How did you make that dramatic?

Ken Loach: What I hope carries the story is that the concept is familiar to most of us. It's the frustration and the black comedy of trying to deal with a bureaucracy that is so palpably stupid, so palpably set to drive you mad. I think if you can tell that truthfully and you're reading the subtext in the relationship between the people across a desk or over a phone line, that should reveal the comedy of it, the cruelty of it – and, in the end, the tragedy of it. -The poor are to blame for their poverty' – this protects the power of the ruling class.

Question: What you were looking for in your Dan and in your Katie when you cast Dave Johns and Hayley Squires?

Ken Loach: Well, for Dan we looked for the common sense of the common man. Every day he's turned up for work, he's worked alongside mates; there's the crack of that, the jokes, the way you get through the day; that's been his life until he was sick and until his wife needed support. And so alongside the sense of humour you want someone quite sensitive and nuanced. And for Katie, again it's someone driven by circumstance who is realistic but has potential; she's been trying to study, she failed at school but she's been studying with the Open University. We looked for someone with sensitivity but also gutsy courage. And, as with Dan, absolute authenticity.

Question: Dave Johns is a stand-up comic as well as an actor. Why did you cast him as Dan?

Ken Loach: The traditional stand-up comedian is a man or woman rooted in working class experience, and the comedy comes out of that experience. It often comes out of hardship, joking about the comedy of survival. But the thing with comedians is they've got to have good timing – their timing is absolutely implicit in who they are. And they usually have a voice that comes from somewhere and a persona which comes from somewhere, so that's what we were looking for. Dave's got that. Dave's from Byker, which is where we filmed some of the scenes, he's a Geordie, he's the right age, and he's a working class man who makes you smile, which is what we wanted.

Question: How did you come to cast Hayley Squires as Katie?

Question: How did you come to cast Hayley Squires as Katie?

Ken Loach: We met a lot of women who were all interesting in different ways but again, Hayley's a woman with a working class background and she was just brilliant. Every time we tried something out she was dead right. She doesn't soften who she is or what she says in any way, she's just true really, through and through.

Question: How was the shoot?

Ken Loach: To begin with, Paul's writing is always very precise, as well as being full of life. This means we rarely shoot material we don't use. The critical thing in filming is planning. It is preparation: working things out; getting everyone cast before you start; getting all the locations in place before you start. To do all that you need a crew, a group of people who absolutely understand the project and are creatively committed to it. And all those things we had: amazing efficiency from everyone and great good humour. That's what gets you through, because it means all your effort is then productive. Working with good friends is a delight and, crucially, we even got a little coffee machine that used to follow us around. That was a key element: a good espresso got us all through the day.

Question: You changed how you edited this film from previous ones. How and why?

Ken Loach: We'd been cutting on film for many years but we found that the infrastructure for cutting on film was just disappearing. The biggest problem was the cost of printing the sound rushes on mag stock and also printing all the film rushes. It was more than I could justify so, reluctantly, we cut on Avid. It has some advantages but I found cutting on film was a more human way of working - you can see what you've done at the end of the day. Avid seems quicker but I don't think the overall time taken is any less. I just find the tactile quality of film is more interesting.

Question: Do you make films hoping to bring about change and, if so, what would that mean in the case of I, Daniel Blake?

Ken Loach: Well it's the old phrase isn't it: -Agitate, Educate, Organise.' You can agitate with a film - you can't educate much, though you can ask questions - and you can't organise at all, but you can agitate. And I think to agitate is a great aim because being complacent about things that are intolerable is just not acceptable. Characters trapped in situations where the implicit conflict has to be played out, that is the essence of drama. And if you can find that drama in things that are not only universal but have a real relevance to what's going on in the world, then that's all the better. I think anger can be very constructive if it can be used; anger that leaves the audience with something unresolved in their mind, something to do, something challenging.

Question: It is the 50th anniversary of Cathy Come Home this year. What parallels are there between this new film and that film?

Question: It is the 50th anniversary of Cathy Come Home this year. What parallels are there between this new film and that film?

I, Daniel Blake

Release Date: November 17th, 2016

MORE